Coloureds

An extended Coloured family with roots in Cape Town, Kimberley and Pretoria | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 5,600,000~ in Southern Africa | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe | |

| 5,052,349 (2022 census)[1] | |

| 107,855 (2023 census)[2][a] | |

| 14,130 (2022 census)[3] | |

| 3,000 (2012 census)[4] | |

| Languages | |

| Afrikaans, English, IsiXhosa, Setswana[5] | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Christianity, minority Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Africans, Mulatto, White South Africans, Afrikaners, Boers, Cape Dutch, Cape Coloureds, Cape Malays, Griquas, San people, Khoikhoi, Zulu, Xhosa, Saint Helenians, Rehoboth Basters, Tswana | |

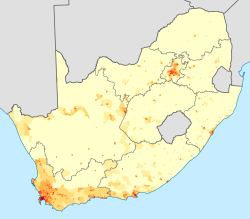

- 0–20%

- 20–40%

- 40–60%

- 60–80%

- 80–100%

- <1 /km2

- 1–3 /km2

- 3–10 /km2

- 10–30 /km2

- 30–100 /km2

- 100–300 /km2

- 300–1000 /km2

- 1000–3000 /km2

- >3000 /km2

Coloureds (Afrikaans: Kleurlinge) are members of multiracial ethnic communities in South Africa, Namibia and to a lesser extent, Zimbabwe and Zambia who have ancestry from African, European, and Asian people. The intermixing of different races began in the Dutch Cape Colony of South Africa, with European settlers intermixing with the indigenous Khoi tribes, and Asian slaves of the region. Later various other European nationals also contributed to the growing mixed race people, who would later be officially classified as coloured by the apartheid government in the 1950s.[7][8]

Coloured was a legally defined racial classification during apartheid referring to anyone not white or of the black Bantu tribes, which effectively largely meant people of colour.[8][9]

In the Western Cape, a distinctive Cape Coloured and affiliated Cape Malay culture developed. Genetic studies suggest the group has the highest levels of mixed ancestry in the world.

The majority of coloureds are found in the Western Cape but are prevalent throughout the country. In Cape Town, they form 43.2% of the total population, according to the South African National Census of 2011.[10]: 11, 57

The apartheid-era Population Registration Act, 1950 and subsequent amendments, codified the Coloured identity and defined its subgroups, including Cape Coloureds and Malays. Indian South Africans were initially classified under the act as a subgroup of Coloured.[11] As a consequence of Apartheid policies and despite the abolition of the Population Registration Act in 1991, Coloureds are regarded as one of four race groups in South Africa. These groups (blacks, whites, Coloureds and Indians) still tend to have strong racial identities and to classify themselves and others as members of these race groups.[9][8] The classification continues to persist in government policy, to an extent, as a result of attempts at redress such as Black Economic Empowerment and Employment Equity.[8][12][13]

Ancestral Background

[edit]South Africa

[edit]South Africa is known as a "Rainbow Nation" because of its massive diversity as a blending pot of many different regions, cultures, races, tribes, religions and nationalities. Due to its massive diversity, Coloured people do not share the same ancestral background, nor do they have the same history because they come from different regions in the country that went through different phases of history.

Dutch Cape Colony/Cape Colony/Cape Province

[edit]Interracial marriages/Miscegenation in South Africa began in the Dutch Cape Colony from the 17th century, shortly after the arrival of Dutch settlers in the Cape(who were led by Jan van Riebeeck). When the Dutch settled in the Cape in 1652, they met the Khoi Khoi who were the natives of the area. [14] The Dutch established farms that required intensive labour therefore, they enforced slavery in the Cape. Some of the Khoi Khoi became labourers while slaves were imported from other parts of the world, most specifically the Bantu people from other parts of Southern Africa and the Malay people from present-day Indonesia. To a smaller extent, there were also slaves imported from Malaysia, Sri Lanka, India, Madagascar, Mauritius and other parts of Africa.

Because almost all the Dutch settlers in the Cape were men, many of them married and conceived mixed-race children with the Khoi Khoi, the Southern African Bantu, the Malay and other groups of slaves in the Cape( such as the Malaysians, the Malagasy people from Madagascar, West Africans, Indians etc). There was also interracial mixing between the slaves and mixed-race children were also conceived from these unions as well because the slaves were of different races(African and Asian). [15]. Unlike the One-drop rule in the USA, mixed race children in the Cape were not viewed as "White enough to be white", "African enough to be African" nor "Asian enough to be Asian". Therefore, mixed race children would grow up and marry amongst themselves forming a community that would eventually be known as the Cape Coloured. [16]

The first interracial marriage in the Cape was between the Krotoa (a Khoi Khoi woman who was a servant, a translator and a crucial negotiator between the Dutch and the Khoi Khoi. Her new name was "Eva Van Meerhof") and Peter Havgard (a Danish surgeon whom the Dutch renamed as "Pieter Van Meerhof").[17] Having conceived 3 mixed-race children, she was known as the mother that gave birth to the Coloured community in South Africa.

With the arrival of more Europeans (such as the French Huguenots, Germans) and the arrival of more African and Asian slaves in the Cape Colony, there were more interracial mixing between the white and the non-white and between the African and Asian slaves and mixed children got absolved into the Cape Coloured community. [18] The predominant Asian slaves in the Cape were the Malay that came from Indonesia. Although most of them got interracially mixed into the Cape Coloured community, a small minority of them have retained their community and culture, therefore, they became known as the Cape Malay. [19]

During the 17th century (in this case, from 1652-1700), the Dutch Cape Colony consisted only of present-day Cape Town with its surrounding areas such as Paarl, Stellenbosch and Franschhoek. However, from the 18th century until the formation of the Union of South Africa in the year, 1910, the territory of the Cape expanded gradually into the North and into the East. This happened, especially after the Trekboers migrated into the Karoo and after British annexation of the Cape in the 19th century. With the expansion of the Cape, there were more interracial mixing between the white and the Khoisans in present-day Northern Cape and between whites and the Xhosa in present-day Eastern Cape.

Interracial unions solely between the European men and Khoi Khoi women in the Cape formed mixed race descendants that became the Griqua people. Most of the Griqua people moved from the Cape to the central region of South Africa which is now Northern Cape where they established a Griqua state called Griqualand West during the mid 19th century.

The Griqua were subjected to an ambiguity of other creole people within Southern African social order. According to Nurse and Jenkins (1975), the leader of this "mixed" group, Adam Kok I, was a former slave of the Dutch governor who was manumitted and provided land outside Cape Town in the eighteenth century.[20] With territories beyond the Dutch East India Company's administration, Kok provided refuge to deserting soldiers, runaway slaves, and remaining members of various Khoikhoi tribes.[21] In South Africa and many neighbouring countries, the white minority governments historically segregated Africans from Europeans after settlement had progressed, and increasingly classified all mixed race people together into a third group, despite their numerous ethnic and national differences in ancestry. The imperial and apartheid governments categorized them as Coloured. In addition, other distinctly homogeneous ethnic groups also traditionally viewed the mixed-race populations as a separate group, and a growing number of mixed-race people also embraced a shared identity.

After British annexation in the early 19th century, slavery was abolished in the Cape, leading to the Great Trek when the Boer left the Cape as Voortrekkers and migrated into the interior of South Africa. Many freed slaves (of which they were now the Cape Coloured) moved to an area in Cape Town that became known as District Six and the turn of the 20th century, District six became more established and populated. Although its population was predominantly Cape Coloured, District Six was diverse with different ethnicities, races and nationalities living there (this includes Blacks, Jews, whites, Asians etc.). Many of these groups got absolved into the Cape coloured community in District.

During the apartheid era in South Africa of the second half of the 20th century, the government used the term "Coloured" to describe one of the four main racial groups it defined by law (the fourth was "Asian," later "Indian"). This was an effort to impose white supremacy and maintain racial divisions. Individuals were classified as White South Africans (formally classified as "European"), Black South Africans (formally classified as "Native", "Bantu" or simply "African" and constituting the majority of the population), Coloureds (mixed-race) and Indians (formally classified as "Asian").[8] The census in South Africa during 1911 played a significant role in defining racial identities in the country. One of the most noteworthy aspects of this census was the instructions given to enumerators on how to classify individuals into different racial categories. The category of "coloured persons" was used to refer to all people of mixed race, and this category included various ethnic groups such as Hottentots, Bushmen, Cape Malays, Griquas, Korannas, Creoles, Negroes, and Cape Coloureds.

Of particular importance is the fact that the instruction to classify "coloured persons" as a distinct racial group included individuals of African descent, commonly referred to as Negroes. Therefore, it is important to note that Cape Coloureds, as a group of mixed-race individuals, also have African ancestry and can be considered as part of the broader African diaspora.[22]

Although the apartheid government recognised various coloured subgroups, including the Cape Malays and Cape Coloureds, the Coloured population, was for many purposes treated as a single group, despite their varying ancestries and cultures. Also during apartheid, many Griqua began to self-identify as Coloureds during the apartheid era, because of the benefits of such classification. For example, Coloureds did not have to carry a dompas (a pass, an identity document designed to limit the movements of the black population), while the Griqua, who were seen as an indigenous African group, though heavily mixed, did.

In the 21st century, Coloured people constitute a plurality of the population in the provinces of Western Cape (48.8%), and a large minority in the Northern Cape (40.3%), both areas of centuries of mixing among the populations. In the Eastern Cape, they make up 8.3% of the population. Most speak Afrikaans, as they were generally descendants of Dutch and Afrikaner men and grew up in their society. About twenty percent of the Coloured speak English as their mother tongue, mostly those of the Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal. Virtually all Cape Town Coloureds are bilingual.[23][24]

Genetics

[edit]At least one genetic study indicates that Cape Coloureds have ancestries from the following ethnic groups. Not all Coloureds in South Africa had the same ancestry.[25]

- Indigenous Khoisan: (32–43%)

- Indigenous Bantu: (20-36%)

- Peoples from Europe: (21–28%)

- Peoples from South and Southeast Asia: (30- 35%).[26][27][28][21]

It is important to note here that genetic reference cluster term "Khoisan" itself refers to a colonially admixed population cluster, hence the concatenation, and is not a straightforward reference to ancient African pastoralist and hunter ancestry, which is often demarcated by the L0 haplogroup ancestry common in the general South African native population which is also integral part of other aboriginal genetic reference cluster terms like "South-East African Bantu".[29]

Colony of Natal/Natal

[edit]Another phase of miscegenation in South Africa happened in the Colony of Natal (present-day KwaZulu-Natal during the 19th century and the early 20th century. This time, it was mainly between the British and the Zulu, with a smaller addition of Indian and Mauritian in the mix. [30]

Zimbabwe

[edit]Zimbabwean Coloureds are descended from Shona or Ndebele, British and Afrikaner settlers, as well as Arab and Asian people.

History

[edit]Pre-apartheid era

[edit]Coloured people played an important role in the struggle against apartheid and its predecessor policies. The African Political Organisation, established in 1902, had an exclusively Coloured membership; its leader Abdullah Abdurahman rallied Coloured political efforts for many years.[31] Many Coloured people later joined the African National Congress and the United Democratic Front. Whether in these organisations or others, many Coloured people were active in the fight against apartheid.

The political rights of Coloured people varied by location and over time. In the 19th century they theoretically had similar rights to Whites in the Cape Colony (though income and property qualifications affected them disproportionately). In the Transvaal Republic or the Orange Free State, they had few rights. Coloured members were elected to Cape Town's municipal authority (including, for many years, Abdurahman). The establishment of the Union of South Africa gave Coloured people the franchise, although by 1930 they were restricted to electing White representatives. They conducted frequent voting boycotts in protest. Such boycotts may have contributed to the victory of the National Party in 1948. It carried out an apartheid programme that stripped Coloured people of their remaining voting powers.

The term "kaffir" is a racial slur used to refer to Black African people in South Africa. While it is still used against black people, it is not as prevalent as it is against coloured people.[32][33]

Apartheid era

[edit]

Coloured people were subject to forced relocation. For instance, the government relocated Coloured from the urban Cape Town areas of District Six, which was later bulldozed. Other areas they were forced to leave included Constantia, Claremont, Simon's Town. Inhabitants were moved to racially designated sections of the metropolitan area on the Cape Flats. Additionally, under apartheid, Coloured people received education inferior to that of Whites. It was, however, better than that provided to Black South Africans.

J. G. Strijdom, known as "the Lion of the North", continued the impetus to restrict Coloured rights, in order to entrench the new-won National Party majority. Coloured participation on juries was removed in 1954, and efforts to abolish their participation on the common voters' roll in the Cape Province escalated drastically; it was accomplished in 1956 by a supermajority amendment to the 1951 Separate Representation of Voters Act, passed by Malan but held back by the judiciary as unconstitutional under the South Africa Act, the Union's effective constitution. In order to bypass this safeguard, enforced since 1909 to ensure Coloured political rights in the then-British Cape Colony, Strijdom's government passed legislation to expand the number of Senate seats from 48 to 89. All of the additional 41 members hailed from the National Party, increasing its representation in the Senate to 77 in total. The Appellate Division Quorum Bill increased the number of judges necessary for constitutional decisions in the Appeal Court from five to eleven. Strijdom, knowing that he had his two-thirds majority, held a joint sitting of parliament in May 1956. The entrenchment clause regarding the Coloured vote, known as the South Africa Act, were thus eliminated and the Separate Representation of Voters Act passed, now successfully.

Coloureds were placed on a separate voters' roll from the 1958 election to the House of Assembly and forward. They could elect four Whites to represent them in the House of Assembly. Two Whites would be elected to the Cape Provincial Council and the governor general could appoint one senator. Both blacks and Whites opposed this measure, particularly from the United Party and more liberal opposition. The Torch Commando was very prominent, while the Black Sash (White women, uniformly dressed, standing on street corners with placards) also made themselves heard. In this way, the question of the Coloured vote became one of the first measures of the regime's unscrupulous nature and flagrant willingness to manipulate its inherited Westminster system. It would remain in power until 1994.

Many Coloureds refused to register for the new voters' roll and the number of Coloured voters dropped dramatically. In the next election, only 50.2% of them voted. They had no interest in voting for White representatives — an activity which many of them saw as pointless, and only persisted for ten years.

Under the Population Registration Act, as amended, Coloureds were formally classified into various subgroups, including Cape Coloureds, Cape Malays and "other coloured". A portion of the small Chinese South African community was also classified as a coloured subgroup.[34][35]

In 1958, the government established the Department of Coloured Affairs, followed in 1959 by the Union for Coloured Affairs. The latter had 27 members and served as an advisory link between the government and the Coloured people.

The 1964 Coloured Persons Representative Council turned out to be a constitutional hitch[clarification needed] which never really got going. In 1969, the Coloureds elected forty onto the council to supplement the twenty nominated by the government, taking the total number to sixty.

Following the 1983 referendum, in which 66.3% of White voters supported the change, the Constitution was reformed to allow the Coloured and Indian minorities limited participation in separate and subordinate Houses in a tricameral Parliament. This was part of a change in which the Coloured minority was to be allowed limited rights and self-governance in "Coloured areas", but continuing the policy of denationalising the Black majority and making them involuntary citizens of independent homelands. The internal rationale was that South African whites, more numerous at the time than Coloureds and Indians combined, could bolster its popular support and divide the democratic opposition while maintaining a working majority. The effort largely failed, with the 1980s seeing increased disintegration of civil society and numerous states of emergency, with violence increasing from all racial groups. The separate arrangements were removed by the negotiations which took place from 1990 to hold the first universal election.

Post-apartheid era

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2021) |

During the 1994 all-race elections, Coloured people voted heavily for the white National Party, which in its first contest with a non-white majority won 20% of the vote and a majority in the new Western Cape province – much due to Cape Coloured support. The National Party recast itself as the New National Party after De Klerk's departure in 1996, partly to attract non-White voters, and grew closer to the ANC. This political alliance, often perplexing to outsiders, has sometimes been explained in terms of the culture and language shared by White and Coloured New National Party members, who both spoke Afrikaans. In addition, both groups opposed affirmative action programmes that might give preference to Black South Africans, and some Coloured people feared giving up older privileges, such as access to municipal jobs, if African National Congress gained leadership in the government. After the absorption of the NNP into the ANC in 2005, Coloured voters have generally drawn to the Democratic Alliance, with some opting for minor parties such as Vryheidsfront and Patricia de Lille's Independent Democrats, with lukewarm support for the ANC.

Since the late 20th century, Coloured identity politics have grown in influence. The Western Cape has been a site of the rise of opposition parties, such as the Democratic Alliance (DA). The Western Cape is considered as an area in which this party might gain ground against the dominant African National Congress. The Democratic Alliance drew in some former New National Party voters and won considerable Coloured support. The New National Party collapsed in the 2004 elections. Coloured support aided the Democratic Alliance's victory in the 2006 Cape Town municipal elections.

Patricia de Lille, who became mayor of Cape Town in 2011 on the platform of the now-defunct Independent Democrats, does not use the label Coloured but many observers would consider her as Coloured by visible appearance. The Independent Democrats party sought the Coloured vote and gained significant ground in the municipal and local elections in 2006, particularly in districts in the Western Cape with high proportions of Coloured residents. The firebrand Peter Marais (formerly a provincial leader of the New National Party) has sought to portray his New Labour Party as the political voice for Coloured people.

Coloured people supported and were members of the African National Congress before, during and after the apartheid era: notable politicians include Ebrahim Rasool (previously Western Cape premier), Beatrice Marshoff, John Schuurman, Allan Hendrickse and Trevor Manuel, longtime Minister of Finance. The Democratic Alliance won control over the Western Cape during the 2009 National and Provincial Elections and subsequently brokered an alliance with the Independent Democrats.

The ANC has had some success in winning Coloured votes, particularly among labour-affiliated and middle-class Coloured voters. Some Coloureds express distrust of the ANC with the comment, saying that the Coloured were considered "not white enough under apartheid and not black enough under the ANC."[36] In the 2004 election, voter apathy was high in historically Coloured areas.[37] The ANC faces the dilemma of having to balance the increasingly nationalistic economic aspirations of its core black African support base, with its ambition to regain control of the Western Cape, which would require support from Coloureds.[13]

Coloureds in other countries of Southern Africa

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2021) |

The term Coloured is also used in Namibia, to describe persons of mixed race, specifically part Khoisan, and part European. The Basters of Namibia constitute a separate ethnic group that are sometimes considered a sub-group of the Coloured population of that country. Under South African rule, the policies and laws of apartheid were extended to what was then called South West Africa. In Namibia, Coloureds were treated by the government in a way comparable to that of South African Coloureds.

In Zimbabwe and to a lesser extent Zambia, the term Coloured or Goffal was used to refer to people of mixed race. Most are descended from mixed African and British, or African and Indian, progenitors. Some Coloured families descended from Cape Coloured migrants from South Africa who had children with local women. Under Rhodesia's predominantly white government, Coloureds had more privileges than black Africans, including full voting rights, but still faced social discrimination. The term Coloured is also used in Eswatini.

Culture

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2023) |

Lifestyle

[edit]As far as family life, housing, eating habits, clothing and so on are concerned, the Christian Coloureds generally maintain a Western lifestyle. Marriages are strictly monogamous, although extramarital and premarital sexual relationships can occur and are perceived differently from family to family. Among the working and agrarian classes, permanent relationships are often officially ratified only after a while if at all.

The average family size of six does not differ from those of other Western families and, as with the latter, is generally related to socio-economic status. Extended families are common. Coloured children are often expected to refer to any extended relatives as their "auntie" or "uncle" as a formality.

While many affluent families live in large, modern, and sometimes luxurious homes, many urban coloured people rely on state-owned economic and sub-economic housing.

Cultural aspects

[edit]There are many singing and choir associations as well as orchestras in the Coloured community. The Eoan Group Theatre Company performs opera and ballet in Cape Town. The Kaapse Klopse carnival, held annually on 2 January in Cape Town, and the Cape Malay choir and orchestral performances are an important part of the city's holiday season. Kaapse Klopse consists of several competing groups that have been singing and dancing through Cape Town's streets on New Year's Day earlier this year. Nowadays the drumlines in cheerful, brightly Coloured costumes perform in a stadium. Christmas festivities take place in a sacred atmosphere but are no less vivid, mainly including choirs and orchestras that sing and play Christmas songs in the streets. In the field of performing arts and literature, several Coloureds performed with the CAPAB (Cape Performing Arts Board) ballet and opera company, and the community yielded three major Afrikaans poets the well-known poets, Adam Small, S.V. Petersen, and P.J. Philander. In 1968, the Culture and Recreation Council was established to promote the cultural activities of the Coloured Community.

Education

[edit]Until 1841 missionary societies provided all the school facilities for Coloured children.

All South African children are expected to attend school from the age of seven to sixteen years, at the minimum.

Economic activities

[edit]Initially, Coloureds were mainly semi-skilled and unskilled labourers who, as builders, masons, carpenters and painters, made an important contribution to the early construction industry in the Cape. Many were also fishermen and farm workers, and the latter had an important share in the development of the wine, fruit and grain farms in the Western Cape.

The Malays were, and still are, skilled furniture makers, dressmakers and coopers. In recent years, more and more Coloureds have been working in the manufacturing and construction industry. There are still many Coloured fishermen, and most Coloureds in the countryside are farm workers and even farmers. The largest percentage of economically active Coloureds is found in the manufacturing industry. About 35% of the economically active Coloured women are employed in clothing, textile, food and other factories.

Another important field of work is the service sector, while an ever-increasing number of Coloureds operate in administrative, clerical and sales positions. All the more professional and managerial posts are. In order to stimulate the economic development of Coloureds, the Coloured Development Corporation was established in 1962. The corporation provided capital to businessmen, offered training courses and undertook the establishment of shopping centres, factories and the like.

Distribution

[edit]A majority of those who identify as Coloured live in the Western Cape, where they make up almost half of the province's population. In the 2022 South African census the distribution of the group per province was as follows:[1]

| Province | Population | % of Coloureds | % of province |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern Cape | 547,741 | 10.84 | 7.58 |

| Free State | 78,141 | 1.55 | 2.64 |

| Gauteng | 443,857 | 8.79 | 2.94 |

| KwaZulu-Natal | 183,019 | 3.62 | 1.47 |

| Limpopo | 18,409 | 0.36 | 0.28 |

| Mpumalanga | 32,100 | 0.64 | 0.62 |

| North West | 60,720 | 1.20 | 1.60 |

| Northern Cape | 563,605 | 11.16 | 41.58 |

| Western Cape | 3,124,757 | 61.85 | 42.07 |

| Total | 5,052,349 | 100.0 | 8.15 |

Language

[edit]Coloured people were some of the first speakers of Afrikaans along with European (Dutch, German and French) colonists and African and Asian slave descendents. The language was originally an informal dialect of Dutch that was spoken amongst the different ethnic slaves to understand each other and also converse with their Dutch masters. Later the language was adopted by white Afrikaners. According to the 2011 South African census, more than 95% of those who identified as Coloured spoke either Afrikaans (74.6%) or English (20.5%) natively, while 4.93% reported a different first language, the most common being Setswana which was spoken by 0.87% of the group.[38]

| Language | Number in 2011 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Afrikaans | 3,442,164 | 74.58% |

| English | 945,847 | 20.49% |

| Setswana | 40,351 | 0.87% |

| isiXhosa | 25,340 | 0.55% |

| isiZulu | 23,797 | 0.52% |

| Sesotho | 23,230 | 0.50% |

| Sign language | 11,891 | 0.26% |

| isiNdebele | 8,225 | 0.18% |

| Sepedi | 5,642 | 0.12% |

| siSwati | 4,056 | 0.09% |

| Tshivenda | 2,847 | 0.06% |

| Xitsonga | 2,268 | 0.05% |

| Sign language | 5,702 | 0.12% |

| Not applicable | 74,043 | 1.60% |

| Total | 4,616,401 | 100.0% |

Cuisine

[edit]Numerous South African cuisines can be traced back to Coloured people. Bobotie, snoek based dishes, koe'sisters, bredies, Malay roti and gatsbies are staple diets of Coloureds and other South Africans as well.[39]

See also

[edit]- Anglo-Indian

- Anglo-Burmese

- Arab-Berber

- Burghers

- Colored

- Culture of South Africa

- Free people of color

- Half-caste

- Indo people

- Khoisan revivalism

- Sandra Laing

- Melungeon

- Mestizo (Mestiço)

- Métis

- Miscegenation

- Mulatto

- One-drop rule

- Pardo

- Passing (racial identity)

- Pencil test

- Person of color

- VOC (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie)

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Census 2022 Statistical Release" (PDF). Statistics South Africa. Retrieved 2024-11-01.

- ^ "Namibia 2023 Population and Housing Census Main Report" (PDF). Namibia Statistics Agency. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ "Zimbabwe 2022 Population and Housing Census Report, vol. 1" (PDF). ZimStat. Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency. p. 122. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2024.

- ^ Milner-Thornton, Juliette Bridgette (2012). The Long Shadow of the British Empire: The Ongoing Legacies of Race and Class in Zambia. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 9–15. ISBN 978-1-349-34284-6.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Alexander, Mary (2019-06-09). "What languages do black, coloured, Indian and white South Africans speak?". South Africa Gateway. Retrieved 2024-06-15.

- ^ Calafell, Francesc; Daya, Michelle; van der Merwe, Lize; Galal, Ushma; Möller, Marlo; Salie, Muneeb; Chimusa, Emile R.; Galanter, Joshua M.; van Helden, Paul D.; Henn, Brenna M.; Gignoux, Chris R.; Hoal, Eileen (2013). "A Panel of Ancestry Informative Markers for the Complex Five-Way Admixed South African Coloured Population". PLOS ONE. 8 (12): e82224. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...882224D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0082224. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3869660. PMID 24376522.

- ^ "coloured". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University. Archived from the original on March 9, 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Posel, Deborah (2001). "What's in a name? Racial categorisations under apartheid and their afterlife" (PDF). Transformation: 50–74. ISSN 0258-7696. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-11-08.

- ^ a b Pillay, Kathryn (2019). "Indian Identity in South Africa". The Palgrave Handbook of Ethnicity. pp. 77–92. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-2898-5_9. ISBN 978-981-13-2897-8.

- ^ Census 2011 Municipal report: Western Cape (PDF). Statistics South Africa. 2012. ISBN 978-0-621-41459-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ^ "1950. Population Registration Act No 30 - the O'Malley Archives".

- ^ "Manyi: 'Over-supply' of coloureds in Western Cape". February 24, 2011.

- ^ a b "BBC News - How race still colours South African elections". BBC News. April 20, 2011. Archived from the original on November 20, 2014.

- ^ mind & who; are & the; cape & coloureds; of & south; africa.

- ^ rvillejenkins & com; profiles & coloured; html.

- ^ academy & lesson; cape & coloureds; origins.

- ^ ac & za; apc & love; time & imperialism; krotoa & eva; van & meerhof.

- ^ sahistory & org; za & dated; event & first; large & group; french & huguenots; arrive & cape.

- ^ sahistory & org; za & article; cape & malay.

- ^ Nurse 1975:71

- ^ a b Palmer, Fileve T. (2015). Through a Coloured Lens: Post-Apartheid Identity amongst Coloureds in KZN (PhD). Bloomington, Ind: Indiana University. hdl:2022/19854.

- ^ Moultrie, A. T., & Dorrington, R. Used for ill, used for good: A century of collecting data on race in South Africa. pp. 7, 8. Moultrie and Dorrington. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232827270_Used_for_ill_used_for_good_A_century_of_collecting_data_on_race_in_South_Africa

- ^ Deumert, Ana (2005). "The unbearable lightness of being bilingual: English–Afrikaans language contact in South Africa" (PDF). Language Sciences. 27 (1): 113–135. doi:10.1016/j.langsci.2004.10.002. ISSN 0388-0001.

- ^ "The Vibrant, Colourful, Coloured People". Encounter.co.za. 2011-09-17. Archived from the original on 2012-06-16. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- ^ de Wit, E; Delport, W; Rugamika, CE; Meintjes, A; Möller, M; van Helden, PD; Seoighe, C; Hoal, EG (August 2010). "Genome-wide analysis of the structure of the South African Coloured Population in the Western Cape". Human Genetics. 128 (2): 145–53. doi:10.1007/s00439-010-0836-1. PMID 20490549. S2CID 24696284.

- ^ Quintana-Murci, L; Harmant, C; H, Quach; Balanovsky, O; Zaporozhchenko, V; Bormans, C; van Helden, PD; et al. (2010). "Strong maternal Khoisan contribution to the South African coloured population: a case of gender-biased admixture". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 86 (4): 611–620. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.02.014. PMC 2850426. PMID 20346436.

- ^ Schlebusch, CM; Naidoo, T; Soodyall, H (2009). "SNaPshot minisequencing to resolve mitochondrial macro-haplogroups found in Africa". Electrophoresis. 30 (21): 3657–3664. doi:10.1002/elps.200900197. PMID 19810027. S2CID 19515426.

- ^ Fynn, Lorraine Margaret (1991). The "Coloured" Community of Durban: A Study of Changing Perceptions of Identity (PDF) (Master of Social Science). Durban: University of Natal.

- ^ Barbieri, Chiara; Vicente, Mário; Rocha, Jorge; Mpoloka, Sununguko W.; Stoneking, Mark; Pakendorf, Brigitte (2013-02-07). "Ancient Substructure in Early mtDNA Lineages of Southern Africa". American Journal of Human Genetics. 92 (2): 285–292. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.12.010. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 3567273. PMID 23332919.

- ^ africa & ata; org & atm; zulu & htm.

- ^ "Dr Abdullah Abdurahman 1872 - 1940". South African History Online. Archived from the original on 2007-11-21. Retrieved 2009-10-23.

- ^ Adhikari, Mohamed, editor. Burdened by Race: Coloured Identities in Southern Africa. UCT Press, 2013, pp. 69, 124, 203 ISBN 978-1-92051-660-4 https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/id/c0a95c41-a983-49fc-ac1f-7720d607340d/628130.pdf.

- ^ Mathabane, M. (1986). Kaffir Boy: The True Story of a Black Youth's Coming of Age in Apartheid South Africa. Simon & Schuster. (Chapter 2)

- ^ An appalling "science"

- ^ Graham Leach, South Africa : no easy path to peace (1986), p. 70: Population Registration Act, 1959 cape coloured

- ^ Welsh, David (2005). "A hollowing-out of our democracy?". Helen Suzman Foundation. Archived from the original on 2011-07-25. Retrieved 2009-10-23.

- ^ Faull, Jonathan (June 21, 2004). "Election Synopsis - How the West was Won (and Lost) - May 2004". Institute for Democracy in Africa. Archived from the original on June 18, 2008. Retrieved 2009-10-23.

- ^ Statistics South Africa: Interactive data "SuperWEB2"; Census 2011 Data (Login required)

- ^ Lagardien, Zainab (2008). Traditional Cape Malay Cooking. Struik Publishers. ISBN 978-1-77007-671-6.

Bibliography

[edit]- Gekonsolideerde Algemene Bibliografie: Die Kleurlinge Van Suid-Afrika, South Africa Department of Coloured Affairs, Inligtingsafdeling, 1960, 79 p.

- Mohamed Adhikari, Not White Enough, Not Black Enough: Racial Identity in the South African Coloured Community, Ohio University Press, 2005, 252 p. ISBN 9780896802445

- Vernie A. February, Mind Your Colour: The "coloured" Stereotype in South African Literature, Routledge, 1981, 248 p. ISBN 9780710300027

- R. E. Van der Ross, 100 Questions about Coloured South Africans, 1993, 36 p. ISBN 9780620178044

- Philippe Gervais-Lambony, La nouvelle Afrique du Sud, problèmes politiques et sociaux, la Documentation française, 1998

- François-Xavier Fauvelle-Aymar, Histoire de l'Afrique du Sud, 2006, Seuil

Novels

[edit]- Pamela Jooste, Dance with a Poor Man's Daughter, Doubleday, 1998, ISBN 978-0-385-40911-7

- Zoë Wicomb, David’s Story, New York, Feminist Press at the City University of New York, 2001.

- Henry Martin Scholtz, A Place Called Vatmaar, 2000, ISBN 978-0795701047