Roberto Clemente

| Roberto Clemente | |

|---|---|

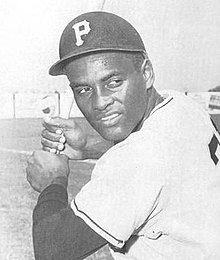

Clemente with the Pirates c. 1961 | |

| Right fielder | |

| Born: August 18, 1934 Barrio San Antón, Carolina, Puerto Rico | |

| Died: December 31, 1972 (aged 38) Off the coast of Isla Verde, Puerto Rico | |

Batted: Right Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| April 17, 1955, for the Pittsburgh Pirates | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| October 3, 1972, for the Pittsburgh Pirates | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Batting average | .317 |

| Hits | 3,000 |

| Home runs | 240 |

| Runs batted in | 1,305 |

| Stats at Baseball Reference | |

| Managerial record at Baseball Reference | |

| Teams | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Member of the National | |

| Induction | 1973 |

| Vote | 92.7% |

| Election method | Special Election |

Roberto Enrique Clemente Walker (Spanish pronunciation: [roˈβeɾto enˈrike kleˈmente (ɣ)walˈkeɾ];[a] August 18, 1934 – December 31, 1972) was a Puerto Rican professional baseball player who played 18 seasons in Major League Baseball (MLB) for the Pittsburgh Pirates, primarily as a right fielder. In December 1972, Clemente died in the crash of a plane he had chartered to take emergency relief goods for the survivors of a massive earthquake in Nicaragua. After his sudden death, the National Baseball Hall of Fame changed its rules so that a player who had been dead for at least six months would be eligible for entry. In 1973, Clemente was posthumously inducted, becoming the first player from the Caribbean and Latin America to be honored in the Hall of Fame.

Born in Carolina, Puerto Rico, Clemente was a track and field star and an Olympic hopeful in his youth before deciding to turn his full attention to baseball. His professional career began at the age of eighteen, with the Cangrejeros de Santurce of the Puerto Rican Professional Baseball League. He quickly attracted the attention of the Brooklyn Dodgers who signed him to a bonus of $10,000. However, due to the bonus rule under which Clemente had signed and the Dodgers decision to send him to the minor leagues, they lost Clemente to the Pittsburgh Pirates who drafted him after the 1954 season.

Clemente was an All-Star for 13 seasons, selected to 15 All-Star Games. He was the National League (NL) Most Valuable Player (MVP) in 1966, the NL batting leader in 1961, 1964, 1965, and 1967, and a Gold Glove Award winner for 12 consecutive seasons from 1961 through 1972. His batting average was over .300 for 13 seasons and he had 3,000 hits during his major league career. He also was a two-time World Series champion. Clemente was the first player from the Caribbean and Latin America to win a World Series as a starting position player (1960), to receive an NL MVP Award (1966), and to receive a World Series MVP Award (1971).

During the offseason, in addition to playing winter ball in Puerto Rico, Clemente was involved in charity work in Latin American and Caribbean countries. In 1972, he died in a plane crash at the age of 38 while en route to deliver aid to victims of the Nicaragua earthquake. The following season, the Pittsburgh Pirates retired his uniform number 21. In his honor, Major League baseball renamed the Commissioner's Award, given to the player who "best exemplifies the game of baseball, sportsmanship, community involvement and the individual's contribution to his team", to the Roberto Clemente Award.

Early life

[edit]Clemente was born on August 18, 1934, in Barrio San Antón in Carolina, Puerto Rico, to Luisa Walker and Melchor Clemente. He was the youngest of seven siblings (three were from his mother's previous marriage). During Clemente's childhood, his father worked as a foreman for sugar cane crops located in the municipality in the northeastern part of the island. Because the family's resources were limited, Clemente and his brothers worked alongside his father in the fields, loading and unloading trucks.[3]

Clemente had first shown interest in baseball early in life and often played against neighboring barrios. When he was fourteen, he was recruited by Roberto Marín to play softball with the Sello Rojo team after he was seen playing baseball in barrio San Antón. He was with the team two years as a shortstop.[4]

He attended Julio Vizcarrondo High School in Carolina where he was a track and field star, participating in the high jump and javelin throw. Clemente was considered good enough to represent Puerto Rico at the Olympics. He later stated that throwing the javelin helped in strengthening his arm and with his footwork and release.[5] Despite his all-around athletic skill, however, Clemente decided to focus on baseball and went on to join Puerto Rico's amateur league, playing for the Ferdinand Juncos team, which represented the municipality of Juncos.[6]

Professional career

[edit]Puerto Rican baseball (1952–1954)

[edit]Clemente's professional career began at age 18 when he accepted a contract from Pedrín Zorrilla with Cangrejeros de Santurce ("Crabbers"), a winter league team and franchise of the Puerto Rican Professional Baseball League (LBPPR). Clemente signed with the team on October 9, 1952. He was a bench player during his first season but was promoted to the Cangrejeros' starting lineup the following season. During this season he hit .288 as the team's leadoff hitter.[7]

While Clemente was playing in the Puerto Rican League, the Brooklyn Dodgers offered him a contract of $15,000 – $10,000 bonus and $5000 league minimum salary. Clemente signed with them on February 19, 1954.[8]

Minor league baseball (1954)

[edit]At the time of Clemente's signing, the bonus rule implemented by Major League Baseball was still in effect. The rule stipulated that when a major league team signed a player to a contract with a signing bonus in excess of $4,000 ($55,000 today), the team was required to keep that player on their 25-man active roster for two full seasons and failure to comply with the rule would result in the team losing the rights to that player's contract, and the player would then be exposed to the waiver wire.[9]

As Clemente's bonus was larger than $4,000, he was considered a bonus baby. However, the Dodgers decided against benching him for two years in the majors and decided to place him with the Montreal Royals, their International League Triple-A affiliate. While it is often believed that the Dodgers instructed manager Max Macon to use Clemente sparingly to prevent him from being drafted under the Rule 5 Draft, Macon himself denied it. Box scores also suggest that Macon platooned Clemente the same as he did with other outfielders.[10]

Affected early on by both climate and language differences, Clemente received assistance from bilingual teammates such as infielder Chico Fernandez and pitchers Tommy Lasorda and Joe Black.[b]

Black was the original target of the Pittsburgh Pirates' scouting trip to Richmond on June 1, 1954. Noticing Clemente in batting practice, Pirates scout Clyde Sukeforth made inquiries and soon learned about Clemente's status as an unprotected bonus baby.[12] Twelve years later, manager Macon acknowledged that "we tried to sneak him through the draft, but it didn't work" but denied being instructed to not play Clemente, stating that the player needed time to develop and was struggling against Triple-A pitching.[13] However, Pittsburgh noticed his raw talents; as Sukeforth recalled years later, "I knew then he'd be our first draft choice. I told Montreal manager Max Macon to take good care of 'our boy' and see that he didn't get hurt."[14]

In 87 games with the Royals, Clemente hit .257 with two home runs.[15] The first home run of his North American baseball career came on July 25, 1954; Clemente's extra inning, walk-off home run was hit in his first at-bat after entering the game as a defensive replacement. His only other minor league home run came on September 5. On his 20th birthday, August 8, he made a notable game-ending outfield assist, cutting down the potential tying run at the plate.[16]

At the end of the season, Clemente returned to play for Santurce where one of his teammates was Willie Mays.[17][18] While with the team, the Pirates made Clemente the first selection of the Rule 5 draft that took place on November 22, 1954.[19]

Major League Baseball (1955–1972)

[edit]For all but the first seven weeks of his major league career, Clemente wore number 21, so chosen because his full name of Roberto Clemente Walker had that many letters.[20] For his first few weeks, Clemente wore the number 13, as his teammate Earl Smith was wearing number 21. It was later reassigned to Clemente.[21]

During the off-seasons (except the 1958–59, 1962–63, 1965–66, 1968–69, 1971–72, and 1972–73 seasons), Clemente played professionally for the Cangrejeros de Santurce, Criollos de Caguas, and Senadores de San Juan in the Liga de Béisbol Profesional de Puerto Rico, where he was considered a star. He sometimes managed the San Juan team.

In September 1958, Clemente joined the United States Marine Corps Reserve. He served his six-month active duty commitment at Parris Island, South Carolina, Camp LeJeune in North Carolina, and Washington, D.C. At Parris Island, Clemente received recruit training with Platoon 346 of the 3rd Recruit Battalion.[22] The rigorous Marine Corps training programs helped Clemente physically; he added strength by gaining ten pounds and said his back troubles, caused by being in a 1954 auto accident, disappeared as a result of the training. He was a private first class in the Marine Corps Reserve until September 1964.[23][24][25]

Early years

[edit]The Pirates struggled through several difficult seasons through the 1950s. They did have a winning season in 1958, their first since 1948.

Clemente debuted with the Pirates on April 17, 1955, wearing uniform number 13, in the first game of a doubleheader against the Brooklyn Dodgers. Early in his career with the Pirates, he was frustrated by racial and ethnic tensions, with sniping by the local media and some teammates. Clemente responded to this by saying "I don't believe in color." He said that, during his upbringing, he was taught never to discriminate against someone based on ethnicity.

Clemente was at a double disadvantage, as he was a Latin American and Caribbean player whose first language was Spanish and was of partially African descent. The year before, the Pirates had hired Curt Roberts, their first African-American player. They were the fifth team in the NL and ninth in the major leagues to do so, seven years after Jackie Robinson broke baseball's color line by joining the Dodgers.[26] When Clemente arrived in Pittsburgh, Roberts befriended him and helped him adjust to life in the major league, as well as in the Pittsburgh area.[27]

During his rookie season, Clemente had to sit out several games, as he had suffered a lower back injury in Puerto Rico the previous winter. A speeding, drunk driver rammed into his car at an intersection. He finished his rookie season with a .255 batting average, despite trouble hitting certain types of pitches. His defensive skills were highlighted during this season.

The following season, on July 25, 1956, at Forbes Field, Clemente erased a three-run, ninth-inning deficit with a bases-clearing inside-the-park home run,[28] thus becoming the first—and, as yet, only—player in modern Major League history (since 1900) to hit a documented walk-off, inside-the-park grand slam.[29] Pittsburgh-based sportswriter John Steigerwald said that it "may have been done only once in the history of baseball."[30]

Clemente was still fulfilling his Marine Corps Reserve duty during spring of 1959 and set to be released from Camp Lejeune until April 4. A Pennsylvania state senator, John M. Walker, wrote to US Senator Hugh Scott requesting an early release on March 4 so Clemente could join the team for spring training.[31]

Stardom

[edit]Early in the 1960 season, Clemente led the league with a .353 batting average, and the 14 extra-base hits and 25 RBIs recorded in May alone resulted in Clemente's selection as the National League's Player of the Month.[32] His batting average would remain above the .300 mark throughout the course of the campaign. On August 5 at Forbes Field, Clemente crashed into the right-field wall while making a pivotal play, depriving San Francisco's Willie Mays of a leadoff, extra-base hit in a game eventually won by Pittsburgh, 1–0. The resulting injury necessitated five stitches to the chin and a five-game layoff for Clemente, while the catch itself was described by Giants beat writer Bob Stevens as "rank[ing] with the greatest of all time, as well as one of the most frightening to watch and painful to make."[33] The Pirates compiled a 95–59 record during the regular season, winning the NL pennant, and defeated the New York Yankees in a seven-game World Series. Clemente batted .310 in the series, hitting safely at least once in every game.[34] His .314 batting average, 16 home runs, and defensive playing during the course of the season had earned him his first spot on the NL All-Star roster as a reserve player, and he replaced Hank Aaron in right field during the 7th and 8th innings in the second All-Star game held that season (two All-Star games were held each season from 1959 through 1962).[35]

During spring training in 1961, following advice from Pirates' batting coach George Sisler, Clemente tried to modify his batting technique by using a heavier bat to slow the speed of his swing. During the 1961 season, Clemente was named the starting NL right fielder for the first of two All-Star games and went 2 for 4; he hit a triple on his first at-bat and scored the team's first run, then drove in the second with a sacrifice fly. With the AL ahead 4–3 in the 10th inning, he teamed with fellow future HOFers Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, and Frank Robinson to engineer a come-from-behind 5–4 NL victory, culminating in Clemente's walk-off single off knuckleballer Hoyt Wilhelm. Clemente started again in right field for the second All-Star game held that season and was 0 for 2, flying and grounding out in the 2nd and 4th innings. That season he received his first Gold Glove Award.[35]

Following the 1961 season, he traveled to Puerto Rico along with Orlando Cepeda, who was a native of Ponce. When both players arrived, they were received by 18,000 people. During this time, he was also involved in managing the Senadores de San Juan of the Puerto Rican League, as well as playing with the team during the major league off-season. During the course of the winter league, Clemente injured his thigh while doing some work at home but wanted to participate in the league's all-star game. He pinch-hit in the game and got a single, but experienced a complication of his injury as a result, and had to undergo surgery shortly after being carried off the playing field. This condition limited his role with the Pirates in the first half of the 1965 season, during which he batted .257. Although he was inactive for many games, when he returned to the regular starting lineup, he got hits in 33 out of 34 games and his batting average climbed up to .340.[35] He participated as a pinch hitter and replaced Willie Stargell playing left field during the All-Star Game on July 15.

Clemente was an All-Star every season he played in the 1960s other than 1968—the only year in his career after 1959 in which he failed to hit above .300—and a Gold Glove winner for each of his final 12 seasons, beginning in 1961. He won the NL batting title four times: 1961, 1964, 1965, and 1967, and won the league's MVP Award in 1966, hitting .317 with a career-high 29 home runs and 119 RBIs. In 1967, Clemente registered a career-high .357 batting average, hit 23 home runs, and batted in 110 runs. Following that season, in an informal poll conducted by Sport Magazine at baseball's Winter Meetings, a plurality of major league GMs declared Clemente "the best player in baseball today," edging out AL Triple Crown winner Carl Yastrzemski by a margin of 8 to 6, with one vote each going to Hank Aaron, Bob Gibson, Bill Freehan and Ron Santo.[36]

In an effort to make him seem more American, sportswriters started calling him "Bob" or "Bobby". His baseball cards even listed him as "Bob Clemente", a practice that persisted through to 1969. He disliked the practice, which he felt was disrespectful to his Puerto Rican and Latino heritage. Clemente would correct reporters who referred to him as "Bob" during post-game interviews, but the issue continued throughout the 1960s.[37]

Final seasons

[edit]The 1970 season was the last one that the Pirates played at Forbes Field before moving to Three Rivers Stadium; for Clemente, abandoning this stadium was an emotional situation. The Pirates' final game at Forbes Field occurred on June 28, 1970. That day, Clemente said that it was hard to play in a different field, saying, "I spent half my life there." The night of July 24, 1970, was declared "Roberto Clemente Night"; on this day, several Puerto Rican fans traveled to Three Rivers Stadium and cheered Clemente while wearing traditional Puerto Rican attire. A ceremony to honor Clemente took place, during which he received a scroll with 300,000 signatures compiled in Puerto Rico, and several thousands of dollars were donated to charity work following Clemente's request.

During the 1970 season, Clemente compiled a .352 batting average; the Pirates won the NL East pennant but were subsequently eliminated by the Cincinnati Reds. During the offseason, Roberto Clemente experienced some tense situations while he was working as manager of the Senadores and when his father, Melchor Clemente, experienced medical problems and underwent surgery.

In the 1971 season, the Pirates won the NL East, defeated the San Francisco Giants in four games to win the NL pennant, and faced the Baltimore Orioles in the World Series. Baltimore had won 101 games (third season in row with 100+ wins) and swept the American League Championship Series, both for the third consecutive year, and were the defending World Series champions. The Orioles won the first two games in the series, but Pittsburgh won the championship in seven games. This marked the second occasion that Clemente helped win a World Series for the Pirates. Over the course of the series, Clemente had a .414 batting average (12 hits in 29 at-bats), performed well defensively, and hit a solo home run in the deciding 2–1 seventh game victory.[38] Following the conclusion of the season, he received the World Series Most Valuable Player Award.[35]

Although he was frustrated and struggling with injuries,[39] Clemente played in 102 games and hit .312 during the 1972 season.[38] He also made the annual NL All-Star roster for the fifteenth (15th) time (he played in 14/15 All-Star games)[40] and won his twelfth consecutive Gold Glove.

On September 30, he hit a double in the fourth inning off Jon Matlack of the New York Mets at Three Rivers Stadium for his 3,000th.[41][42] It was his last regular season at-bat of his career. By playing in right field in one more regular season game, on October 3, Clemente tied Honus Wagner's record for games played as a Pittsburgh Pirate, with 2,433 games played. In the NL playoffs that season, he batted .235 as he went 4 for 17. His last game was October 11, 1972, at Cincinnati's Riverfront Stadium in the fifth and final game of the 1972 NLCS, won by the Reds in the bottom of the 9th inning. Clemente had his final hit (single) in the 1st inning; his final plate appearance was an intentional walk in the 8th inning.[38] He and Bill Mazeroski were the last Pirate players remaining from the 1960 World Series championship team.

Charity work and death

[edit]Clemente spent much of his time during the off-season involved in charity work. He also visited Managua, the capital city of Nicaragua, in late 1972, while managing the Puerto Rico national baseball team at the 1972 Amateur World Series.[43] When Managua was affected by a massive earthquake three weeks later, on December 23, 1972, Clemente immediately set to work arranging emergency relief flights.[44] He soon learned, however, that the aid packages on the first three flights had been diverted by corrupt officials of the Somoza government, never reaching victims of the quake.[45] He decided to accompany the fourth relief flight, hoping that his presence would ensure that the aid would be delivered to the survivors.[46]

The airplane which he chartered for the New Year's Eve flight, a Douglas DC-7 cargo plane, had a history of mechanical problems and it also had an insufficient number of flight personnel (the flight was missing a flight engineer and a copilot), and it was also overloaded by 4,200 pounds (1,900 kg).[47] It crashed into the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Isla Verde, Puerto Rico immediately after takeoff on December 31, 1972, due to engine failure.[48]

A search and rescue effort was immediately launched, led by the USCGC Sagebrush.[49] A few days after the crash, the body of the pilot and part of the fuselage of the plane were found. An empty flight case which apparently belonged to Clemente was the only personal item of his which was recovered from the plane. Clemente's teammate and close friend Manny Sanguillén was the only member of the Pirates who did not attend Roberto's memorial service. Instead, the Pirates catcher chose to dive into the waters where Clemente's plane had crashed in an effort to find his teammate. The bodies of Clemente and three others who were also on the four-engine plane were never recovered.[48]

Montreal Expos pitcher Tom Walker, then playing winter league ball in Puerto Rico, had helped him load the plane. Because Clemente wanted Walker, who was single, to go and enjoy New Year's Eve,[50] Clemente told him not to join him on the flight. A few hours later, Walker returned to his condo and discovered that the plane carrying Clemente had crashed.[51]

In an interview for the ESPN documentary series SportsCentury in 2002, Clemente's widow Vera mentioned that Clemente had told her that he thought he was going to die young several times.[26] Indeed, while he was being asked when he would get his 3,000th career hit by broadcaster and future fellow Hall of Famer Richie Ashburn in July 1971 during the All-Star Game activities, Clemente's response was "Well, uh, you never know. I, I, uh, if I'm alive, like I said before, you never know because God tells you how long you're going to be here. So you never know what can happen tomorrow."[52]

Career overall

[edit]At the time of his death, Clemente had established several records with the Pirates, including most triples in a single game (three) and hits in two consecutive games (ten).[53] He won 12 Gold Glove Awards and shares the record of most won among outfielders with Willie Mays.[54][55]

Clemente was an All-Star for 13 seasons, selected to 15 All-Star Games.[c] He won the NL MVP Award in 1966, and was named NL Player of the Month Award three times (May 1960, May 1967, July 1969). Clemente led the Pirates to two World Series titles, being named World Series MVP in 1971.[35]

Clemente had two three-home run games in his career, as well as eight five-hit games in MLB.[57]

| Category | G | BA | AB | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | SB | CS | BB | SO | OBP | SLG | OPS | E | A | PO | FLD% | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 2,433 | .317 | 9,454 | 1,416 | 3,000 | 440 | 166 | 240 | 1,305 | 83 | 46 | 621 | 1,230 | .359 | .475 | .834 | 142 | 269 | 4,796 | .972 | [35] |

Honors and legacy

[edit]

On March 20, 1973, the Baseball Writers' Association of America held a special election for the Baseball Hall of Fame. They voted to waive the waiting period for Clemente, due to the circumstances of his death, and posthumously elected him for induction into the Hall of Fame, giving him 393 out of 424 available votes, for 92.7% of the votes.[d][60]

Clemente's number 21 was retired by the Pittsburgh Pirates on April 6, 1973, a few months after his election to the Hall of Fame.[61][62] There have been calls for MLB to retire number 21 league-wide, as was done with Jackie Robinson's number 42 in 1997, but the sentiment has been opposed by the Robinson family.[63]

In 1999, Clemente was ranked number 20 on The Sporting News list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players, the highest-ranking Latin American and Caribbean player on the list.[64] Later that year, he was nominated as a finalist for the Major League Baseball All-Century Team.[65] In 2020, The Athletic ranked Clemente at number 40 on its "Baseball 100" list, complied by sportswriter Joe Posnanski.[66]

In 2007, Clemente was selected for the All Time Rawlings Gold Glove Team for the 50th anniversary of the creation of the Gold Glove Award.[67]

He was named to Major League Baseball's Latino Legends Team in 2005.[68]

In 1973, Major League Baseball renamed the Commissioner's Award to the Roberto Clemente Award. It has been awarded every year to a player with outstanding baseball playing skills who is personally involved in community work. A trophy and a donation check for a charity of the player's choice are presented annually at the World Series.[69]

Clemente was elected to the Hispanic Heritage Baseball Museum Hall of Fame in 2010,[70] and the Caribbean Baseball Hall of Fame in 2015. In 2003, he was also inducted into the United States Marine Corps Sports Hall of Fame.[71]

Near the old Forbes Field where Clemente began his major league career, the city of Pittsburgh renamed a street in his honor.[72] Additionally, the city named Roberto Clemente Memorial Park in his honor. At Pirate City, the Pirates spring training home in Bradenton, Florida, a section of 27th Street East is named Roberto Clemente Memorial Highway.[73]

The United States Postal Service issued a Roberto Clemente postal stamp on August 17, 1984.[74] The stamp was designed by Juan Lopez-Bonilla and shows Clemente wearing a Pittsburgh Pirates baseball cap with a Puerto Rican flag in the background.[75]

The Pirates originally erected a statue in memory of Clemente at Three Rivers Stadium, just before the 1994 Major League Baseball All-Star Game. It has since been moved to PNC Park when it opened in 2001, and stands outside the park's centerfield gates.[76]

In 1974, the Harlem River State Park in Morris Heights, The Bronx, New York City, was renamed Roberto Clemente State Park in his honor. In 2013, forty years after his election to the Hall of Fame, a statue was unveiled at the park. It was the first statue honoring a Puerto Rican to be unveiled in New York City.[77]

In 2012, the Puerto Rico Professional Baseball League (LBPPR) was renamed Liga de Béisbol Profesional Roberto Clemente, the number 21 was also permanently retired.[78]

A number of schools have been named after Clemente, including the Roberto Clemente Community Academy in Chicago,[79] and the Roberto Clemente Charter School in Allentown, Pennsylvania.[80]

In 2002, 30 years after his death, Major League Baseball proclaimed September 15 as "Roberto Clemente Day".[81]

In 1973, President Richard Nixon posthumously honored Clemente with the Presidential Citizens Medal.[82] That same day, Congress honored Clemente with the Congressional Gold Medal.[83] In 2003, President George W. Bush awarded Clemente the Presidential Medal of Freedom.[84]

Clemente is an iconic sports figure in Puerto Rico, widely revered by his people. In 2022, the government of Puerto Rico granted Clemente the formal recognition of prócer (national hero).[85] The Coliseo Roberto Clemente, opened in 1973 in San Juan, and Estadio Roberto Clemente, opened in 2000 in Carolina, are both named in his honor.[86]

Personal life

[edit]Clemente was married on November 14, 1964 to Vera Zabala at San Fernando Church in Carolina. The couple had three children: Roberto (often referred to as "Roberto Jr."), born in 1965; Luis Roberto, born in 1966; and Roberto Enrique, born in 1969.[87] Vera Clemente died on November 16, 2019, aged 78.[88][89]

Clemente was a devout Catholic.[90] In the 2010s, there was an initiative to have him canonized by the Catholic Church.[91][92]

See also

[edit]- List of Gold Glove Award winners at outfield

- List of baseball players who died during their careers

- List of Major League Baseball batting champions

- List of Major League Baseball annual triples leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career doubles leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career home run leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career batting average leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career hits leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career extra base hits leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs batted in leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career total bases leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career triples leaders

- List of Major League Baseball players from Puerto Rico

- List of Major League Baseball players who spent their entire career with one franchise

- List of Puerto Rican Presidential Citizens Medal recipients

- List of Puerto Rican Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

Notes

[edit]- ^ Both a 1955 interview with Clemente and a 1994 interview with his wife Vera confirm that Clemente's full name includes the middle name, Enrique. The discrepancy in spelling – 1994's 'Enrique' vs. 1955's E-n-r-i-c-q-u-e (as allegedly spelled out for the interviewer by Clemente) – is presumably due to a misunderstanding on the part of the Post-Gazette's non-Spanish-speaking interviewer, likely mistaking the word "Si" for the letter c.[1][2]

- ^ To what extent Lasorda assisted Clemente is open to debate. Fellow Royals hurler Joe Black categorically denies Lasorda's characterization of Clemente as unable to "speak one word of English":

"I saw him on the field and I said, 'Tommy, why did you tell that story?' He said, 'What do you mean?' I said, 'One: Clemente didn't hang out with you. Second: Clemente speaks English.' ... Puerto Rico, you know, is part of the United States. So, over there, youngsters do have the privilege of taking English in classrooms. He wouldn't give a speech like Shakespeare, but he knew how to order breakfast and eggs. He knew how to say, 'it's a good day,' 'let's play,' or 'why I don't play?' He could say, 'Let's go to the movies.'"[11]

- ^ Major League Baseball held two All-Star Games for the years from 1959 to 1962.[56]

- ^ Clemente's Hall of Fame plaque originally had his name as "Roberto Walker Clemente" instead of the proper Spanish format "Roberto Clemente Walker"; the plaque was recast in 2000 to correct the error.[58] Both plaques are currently on display in the Hall of Fame, the new one in the plaque gallery and the original in the “sandlot kids clubhouse” area.[59]

References

[edit]- ^ Abrams, Al (June 7, 1955). "Sidelight on Sports: A Baseball Star is Born". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- ^ O'Brien, Jim (1994). Remember Roberto: Clemente Recalled by Teammates, Family, Friends, and Fans. James P. O'Brien Publishing. p. 54. ISBN 0-916114-14-7.

- ^ "Roberto Clemente (SABR BioProject)". Society for American Baseball Research.

Roberto Clemente Walker was born on August 18, 1934, to Melchor Clemente and Luisa Walker de Clemente in Carolina, which is slightly east of the Puerto Rican capital of San Juan. Roberto was the youngest of Luisa's seven children (three of whom were from a previous marriage).

- ^ "Roberto Clemente (SABR BioProject)". Society for American Baseball Research.

When he was 14 years old Roberto joined a softball team organized by Roberto Marín, who became very influential in Clemente's life. Marín noticed Roberto's strong throwing arm and began using him at shortstop. He eventually moved him to the outfield.

- ^ "Roberto Clemente (SABR BioProject)". Society for American Baseball Research.

Throwing the javelin strengthened his arm and helped him in other ways, according to one of his biographers, Bruce Markusen: "The footwork, release, and general dynamics employed in throwing the javelin coincided with the skills needed to throw a baseball properly. The more that Clemente threw the javelin, the better and stronger his throwing from the outfield became."

- ^ Maraniss, pp. 25-26.

- ^ Maraniss, pp. 27.

- ^ Maraniss, pp. 36-38.

- ^ "MLB Bonus Babies". Baseball Almanac.

- ^ "Max Macon (SABR BioProject)". Society for American Baseball Research.

Brooklyn general manager Buzzie Bavasi later acknowledged that the team hoped to hide Clemente so no other team would see his incandescent talent and draft him — as Pittsburgh did after the season... Researcher Stew Thornley found that Clemente was platooned for much of the season, starting only against left-handed pitchers, just as Macon platooned other outfielders.

- ^ Markusen, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Markusen, p. 23.

- ^ "Max Macon (SABR BioProject)". Society for American Baseball Research.

Macon always denied it, but he was not believed... "I never had any orders not to play Clemente," Macon said.

- ^ Biederman, Les (July 29, 1956). "Bob Clemente Discovered by Clyde Sukeforth". The Pittsburgh Press. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- ^ "Roberto Clemente Minor League Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "Clemente's Toss helps Beat Toronto". Montreal Gazette. UPI. August 19, 1954.

- ^ Maraniss, pp. 54–58.

- ^ Monagan, Matt (December 28, 2023). "Mays, Clemente in the same outfield? It happened". MLB.com.

- ^ Schoenfield, David (September 16, 2015). "How the Pirates stole Roberto Clemente from the Dodgers". ESPN.

- ^ Ziants, Steve (April 3, 2016). "The History: Back Stories in Time; Things We Thought We Knew (Or Never Thought About)". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- ^ Biederman, Les (May 25, 1955). "The Scoreboard". The Pittsburgh Press.

- ^ Maraniss, p. 88.

- ^ "Clemente to Start Six-Month Marine Corps Hitch, October 4". The Sporting News. September 24, 1958. p. 7.

- ^ "Buc Flyhawk Now Marine Rookie". The Sporting News. November 19, 1958. p. 13.

- ^ "Marine Corps Sports Hall of Fame – Roberto Clemente". Archived from the original on September 30, 2007.

- ^ a b SportsCentury: Roberto Clemente

- ^ Bouchette, Ed (May 15, 1987). "Roberts Bucs' forgotten pioneer". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. pp. 19, 22. Retrieved March 10, 2012.

- ^ Hernon, Jack (July 26, 1956). "Bucs Bounce Back After Losing Lead". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ McEntire, Madison (2006). Big League Trivia: Facts, Figures, Oddities, and Coincidences from Our National Pastime. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse. p. 52–53. ISBN 1-4259-1292-3. See also:

- McEntire, op. cit., p. ix.

- ^ Steigerwald, John (July 23, 2006). "This Was Clemente's Grandest Slam". Indiana Gazette. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

On July 25, 1956, Roberto Clemente did something that may have been done only once in the history of baseball. And I was there to see it

- ^ "Roberto Clemente, A Legacy Beyond Baseball". Pieces of History. July 17, 2014. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

- ^ "Clemente NL's 'Best in May': Roberto Solid Choice for Award". The Pittsburgh Press. United Press International. June 4, 1960.

- ^ Stevens, Bob (August 6, 1960). "Spectacular Game: Virdon Circles Bases on Error". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ "Clemente: Baseball's Biggest Bargain". Chicago Tribune. Associated Press. January 2, 1973.

- ^ a b c d e f "Roberto Clemente Career Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ Markusen, p. 171.

- ^ Markusen, Bruce. "Clemente overcame societal barriers en route to superstardom". National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

- ^ a b c Larry Schwartz. "Clemente quietly grew in stature". ESPN. Retrieved December 9, 2007.

- ^ "Ankles keeping Clemente down". The Spokesman-Review. Associated Press. August 15, 1972. p. 15.

- ^ Official Pittsburgh Pirates Site, Roberto Clemente – #21, "12-time All-Star" [1] Archived February 1, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved September 20, 2015

- ^ Smizik, Bob (October 1, 1972). "Roberto gets 3,000th, will rest until playoffs". The Pittsburgh Press. p. D1.

- ^ "Roberto Clemente Award". Major League Baseball. Retrieved December 9, 2007.

- ^ "Veteran Cuban Team Captures Amateur Title; U.S. Runner-Up". The Sporting News. December 30, 1972. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ "White House Dream Team: Roberto Walker Clemente". White House. Archived from the original on December 16, 2007. Retrieved December 9, 2007.

- ^ "El vuelo solidario y temerario de Clemente". El Nuevo Diario. Archived from the original on February 4, 2009. Retrieved December 9, 2007.

- ^ "Hispanic Heritage: Roberto Clemente". Gale Gengage Learning. Archived from the original on December 23, 2007. Retrieved December 9, 2007.

- ^ Bryant, Ted (July 13, 1973). "Roberto Clemente plane ruled unfit". Nashua Telegraph. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- ^ a b "Roberto Clemente". Latino Legends in Sports. Archived from the original on October 26, 2007. Retrieved December 9, 2007.

- ^ United Press International (January 1, 1973). "Clemente dies in crash". UPI Archives. Retrieved October 3, 2022.

- ^ Kepner, Tyler (September 1, 2013). "Pittsburgh's Stirring Leap From the Abyss". The New York Times.

- ^ McCalvy, Adam (September 7, 2017). "Tom Walker recalls memories of Clemente". MLB.com.

- ^ "Roberto Clemente Prophecy". YouTube. November 8, 1973. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- ^ "Pirates Single Game Records". Pittsburgh Pirates. Archived from the original on March 9, 2007. Retrieved January 9, 2008.

- ^ "Gold Glove National League Outfielders". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved January 9, 2008.

- ^ "Most Gold Gloves (by position)". Sandbox Networks, Inc./Infoplease. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ Sandomir, Richard (July 15, 2008). "When Midsummer Had Two Classics". The New York Times.

- ^ "Top Performances for Roberto Clemente". Retrosheet.

- ^ "Clemente's Plaque Corrected". The New York Times. September 20, 2000.

- ^ Lukas, Paul (July 23, 2009). "Jeff Idelson: Baseball Hall of Fame president talks about caps, typos and more". ESPN.

- ^ Anapolis, Nick. "Clemente elected to Hall of Fame only months after crash". National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

- ^ "Pirates Retired Numbers". MLB.com.

- ^ Jordan, Jimmy (April 7, 1973). "Misty Scene: Bucs Retire No. 21". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- ^ "Sharon Robinson: honor Clemente some other way". ESPN. Associated Press. January 24, 2006. Retrieved August 17, 2009.

- ^ "Baseball's 100 Greatest Players: No. 20, Roberto Clemente". The Sporting News. April 26, 1999. Archived from the original on January 30, 2005.

- ^ "All-Century Team final voting". ESPN. October 23, 1999. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ Posnanski, Joe (February 16, 2020). "The Baseball 100: No. 40, Roberto Clemente". The Athletic.

- ^ "Rawlings All-Time Gold Glove Team". Baseball Almanac.

- ^ "Chevrolet Presents the Major League Baseball Latino Legends Team unveiled today". MLB.com. October 26, 2005. Archived from the original on June 30, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ "Roberto Clemente Award". Baseball Almanac.

- ^ "Heritage Baseball Museum Hall of Fame". hispanicheritagebaseballmuseum.org. Archived from the original on January 6, 2016. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ "Roberto Clemente: A Veteran Worthy of Honor". Roberto Clemente Foundation.

- ^ Cheney, Jim (March 21, 2020). "Uncovering the Remnants of Forbes Field in Pittsburgh". Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ Anderson, Chris (February 25, 2012). "Signs of Roberto Clemente remain in Bradenton". Herald Tribune. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ "National Postal Museum to feature Roberto Clemente Walker". Hispania News. Archived from the original on February 3, 2009. Retrieved December 10, 2007.

- ^ Oliver, Tony. "Roberto Clemente Postage Stamps Across the World". Society for American Baseball Research.

- ^ "Statue dedicated to Clemente". United Press International. July 8, 1991.

- ^ Gonzalez, David (June 28, 2013). "A New Home for Clemente: On a Pedestal in the Bronx". The New York Times. Retrieved May 21, 2024.

- ^ "Nace la Liga de Béisbol Profesional Roberto Clemente". Primera Hora. May 19, 2012.

- ^ "About Us". Roberto Clemente Community Academy.

- ^ "Home". Roberto Clemente Charter School.

- ^ "MLB celebrates Roberto Clemente Day". MLB.com. September 14, 2022.

- ^ "Remarks at a Ceremony Honoring Roberto Clemente, May 14, 1973". The American Presidency Project. Archived from the original on July 19, 2018. Retrieved July 11, 2013.

- ^ "The Roberto Clemente Walker Congressional Gold Medal". History, Arts & Archives. U.S. House of Representatives. Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- ^ "Remarks on Presenting the Presidential Medal of Freedom, July 23, 2003". The American Presidency Project. Archived from the original on July 19, 2018.

- ^ "A casi 50 años de su muerte, dan a Roberto Clemente el título de prócer de Puerto Rico" (in Spanish). Primera Hora. August 18, 2022. Retrieved August 28, 2022.

- ^ Krueger, Justin. "Remembrance and Iconography of Roberto Clemente in Public Spaces". Society for American Baseball Research.

- ^ "Clemente's Family and Legacy". PBS.

- ^ "Vera Clemente, widow of Pirates legend, dies at age 78". ESPN. November 16, 2019. Retrieved November 16, 2019.

- ^ Seelye, Katharine Q. (November 18, 2019). "Vera Clemente, Flame-Keeping Widow of Baseball's Roberto, Dies at 78". The New York Times.

- ^ Doino, William (January 14, 2013). "The Christian Witness of Roberto Clemente". firstthings.com. Retrieved March 5, 2023.

- ^ Adams, Heather (June 17, 2014). "Roberto Clemente, the next saint?". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 25, 2015.

- ^ Snyder, Matt (June 12, 2015). "Saint Roberto? There's a canonization movement for Clemente". CBS Sports.

Book sources

[edit]- Maraniss, David (2006). Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball's Last Hero. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0743299992.

- Markusen, Bruce (1998). Roberto Clemente: The Great One. Sports Publishing. ISBN 978-1613213483.

Further reading

[edit]Articles

[edit]- Hernon, Jack (May 6, 1955). "Roamin' Around: The Kid They'll Talk About". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- Biederman, Les (May 27, 1959). "Clemente Belts Tape-Measure Homer at Wrigley Field". The Sporting News.

- Cernkovic, Rudy (May 28, 1960). "Roberto Clemente Is Often Compared with Willie Mays". Memphis World. UPI.

- Prato, Lou (June 5, 1962). "Rival Pitchers Look Out! Clemente very sick man". Oxnard Press-Courier. AP.

- Schuyler, Ed (August 11, 1964). "Clemente Unorthodox? Well, He Gets Results". The Daytona Beach Morning Journal. AP.

- Cope, Myron (March 7, 1966). "Aches and Pains and Three Batting Titles". Sports Illustrated.

- Richman, Milton. "Roberto Clemente Tells Them All What's What". Desert Sun. March 11, 1966

- Biederman, Les. "Clemente Bombs Mets: Roberto Socks 500-Foot Homer". The Pittsburgh Press. March 25, 1966.

- Biederman, Les. "The Scoreboard: Big Day For Two Pirates; Clemente's Friend Retrieves Ball; Longest Drive In Wrigley Field". The Pittsburgh Press. June 6, 1966.

- Biederman, Les. "Cards Survive Clemente's HR Blast; Roberto Raps 450-Footer In 4-2 Loss". The Pittsburgh Press. June 10, 1966.

- Chass, Murray (AP). "Donn Drags, Not Clemente". The Tuscaloosa News. June 14, 1966.

- Feeney, Charley. "Roamin' Around: Is He Really the Great Roberto?". The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. August 19, 1966.

- Couch, Dick (AP). "Clemente Waves Banner for Spanish-Speaking Players: Don't Get Due Recognition". The Sarasota Herald-Tribune. August 23, 1966.

- Biederman, Les. "Roberto's Bat Softens Rivals; Clemente Clouts Clutch HR for 2,000th Hit". The Sporting News. September 17, 1966.

- Biederman, Les."Roberto's Rifle Wing Amazes Fans, Shoots Down Cards, Amazes Fans". The Sporting News. July 1, 1967.

- Hano, Arnold. "Roberto Clemente, Baseball's Brightest Superstar". Boys' Life. March 1968.

- "The Strain of Being Roberto Clemente: A beaseball superstar frustrated by faint praise". Life. May 24, 1968.

- Richman, Milton. "Ailing Shoulder Bothers Roberto: Loves Baseball Too Much to Quit". Desert Sun. August 14, 1968.

- Wilson, John. "Standing Cheer for Roberto". The Sporting News. February 20, 1971.

- Abrams, Al. "Sidelights on Sports: I Remember Roberto". The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. January 2, 1973. pp. 14, 17.

- Wulf, Steve (December 28, 1992). "December 31: ¡Arriba Roberto!". Sports Illustrated.

- Wulf, Steve (September 19, 1994). "25 Roberto Clemente". Sports Illustrated.

Books

[edit]- Hano, Arnold (1973). Roberto Clemente, Batting King. G.P. Putnam's Sons. OCLC 762748.

- Musick, Phil (1974). Who Was Roberto? A Biography of Roberto Clemente. Associated Features, Inc. ISBN 9780385084215.

- O'Brien, Jim (1994). Remembering Roberto: Clemente Recalled by Teammates, Family, Friends and Fans. James P. O'Brien. ISBN 9780916114145.

- Markusen, Bruce (2009). The Team That Changed Baseball: Roberto Clemente and the 1971 Pittsburgh Pirates. Westholme Publishing. ISBN 978-1594160899.

- Freedman, Lew (2011). Roberto Clemente: Baseball Star & Humanitarian: Baseball Star And Humanitarian. Sportszone. ISBN 978-1617147548.

- Santiago, Wilfred (2011). 21: The Story of Roberto Clemente. Fantagraphics Books. ISBN 978-1606997758.

External links

[edit]- Career statistics from MLB, or ESPN, or Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball Reference (Minors), or Retrosheet, or Beisbol 101

- Roberto Clemente Foundation

- Roberto Clemente at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Roberto Clemente at the SABR Baseball Biography Project

- Roberto Clemente at IMDb

- Roberto Clemente

- 1934 births

- 1972 deaths

- Cangrejeros de Santurce (baseball) players

- Congressional Gold Medal recipients

- Expatriate baseball players in Nicaragua

- Gold Glove Award winners

- Liga de Béisbol Profesional Roberto Clemente outfielders

- Major League Baseball players from Puerto Rico

- Major League Baseball players with retired numbers

- Major League Baseball right fielders

- Missing air passengers

- Montreal Royals players

- National Baseball Hall of Fame inductees

- National League All-Stars

- National League batting champions

- National League Most Valuable Player Award winners

- Pittsburgh Pirates players

- Presidential Citizens Medal recipients

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Puerto Rican expatriate baseball players in Canada

- Puerto Rican people of African descent

- Puerto Rican Roman Catholics

- Puerto Rican United States Marines

- Sportspeople from Carolina, Puerto Rico

- United States Marine Corps reservists

- Victims of aviation accidents or incidents in 1972

- Victims of aviation accidents or incidents in Puerto Rico

- World Series Most Valuable Player Award winners